Overconsumption or ‘simply’ consumption?

Fair resource use, or resource depletion?

Fair share, equal share or acquired share of resources?

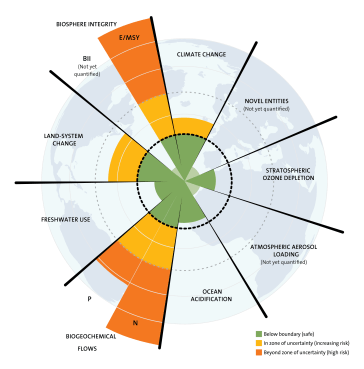

Those are questions that pop up when the Planetary Boundaries are being discussed.

And to an extent rightly so. There is little tangible evidence of who exactly overconsumes (goods or resources) and to what extent. We generally accept the fact that ‘the global North’ is probably the worst in doing so on average.

Yet – what does that mean more concretely?

Can we have a better idea of the order of magnitude of the Western world’s footprint overshoot?

“Is Europe living within the limits of our planet?: An assessment of Europe’s environmental footprints in relation to planetary boundaries”, published in April 2020 by the European Environmental Agency (AAE) and the Swiss Federal Office for the Environment (FOEN) does exactly that: it evaluates and calculates the European performance for planetary boundaries by taking a consumption-based (footprint-based) perspective. This is turn is interesting as it relates environmental pressures to final demands for goods and services.

The study addresses three planetary boundaries in a European-scale analysis:

- phosphorus cycles

- nitrogen cycles

- land system change and

- freshwater use

Interestingly, while the biogeochemical flows of phosphorus and nitrogen are part of the same planetary boundary, the study breaks them further down and addresses them as two separate Earth system processes.

Additionally, and to give a feel for how that might look like also at European level, a case study for Switzerland on biosphere integrity (genetic diversity) is also included.

Equally fascinating:

So far, the few existing academic studies that have tried their hand to come up with ‘some’ overarching picture of how Europe (or any other geographical entity, be it region or country) performs relative to the planetary boundaries, typically used the ‘equality principle’ to first calculate the fraction of the global boundary resources that are the save space’ (for their geography of choice, and then the performance relative to that fraction.

The equality principle assumes basic idea of equal rights for all humans on Earth.

This effort goes much further, and rather to delve into the issue of whether the equality principle is justified or any good, the calculations were completed by exploring multiple allocation principles to define boundary shares. The additional principle used thereby were: human needs, right to development, sovereignty, and capability (cf. Table 3.1 from the report, available hereafter).

Only then once the European share based on any one of the 4 allocation methods the actual European limits for the above mentioned planetary boundaries were selected.

The study insights – A stark call to action

The results are rather … shall we say outside of any comfort zone:

A comparison of European footprints with European limits for the selected planetary boundaries shows that the European footprints exceed the European limits for three out of four Earth system processes, namely for

- the nitrogen cycle:

European limit for nitrogen losses is exceeded by a factor of 3.3. In comparison, the global limit for nitrogen losses is exceeded by a factor of 1.7. - the phosphorus cycle:

the European limit for phosphorus losses is exceeded by a factor of 2. In comparison, the global limit for phosphorus losses is also exceeded by a factor of 2 - land system change:

the European limit for land cover anthropisation is exceeded by a factor of 1.8. In comparison, the global limit for land cover anthropisation is not exceeded.

Only for fresh water use Europe finds itself within its rightful share on average: the European freshwater footprint is below the European limit by a factor of 3. In comparison, the global freshwater footprint is below the global limit by a factor of 3.3.

However, this does neither mean that local overconsumption of freshwater may not occur, nor that some European regions may not suffer more droughts.

Equally interesting, but not very uprising is the following insight:

The largest shares of many countries’ environmental footprints occur abroad. This is particularly the case for small open economies such as Switzerland. Taking such indirect environmental pressures into account is an indispensable.

What does that mean for Europeans?

For Europeans – brands and consumers alike – the message is clear:

Resource use and material flows throughput needs to be drastically reduced.

For the dimensions measured: down to about one third (1/3) of today’s measures.

The shocking part of that?

Do not even get cheated into assuming that this is possible via the coveted terminology of ‘sustainable growth’. Growth invariably means quantitatively increasing measures.

The insights from the report clearly indicate: Not only are we in Europe above and beyond the systemic carrying capacity of our own (geographical, natural) area. But we offload most of that to overseas jurisdictions – who already are challenged in their own rights.

No – it is now all about ‘sustainable development’. Or in other words: more quality and less quanitity.

And no, new tech etc will not make that happen.

The only thing that will make that happen is an economy where the welfare of people and the planet is put at least at an equal level of economy. And where blatant accummulation of resources (incl. Capital) at the expense of people and natural resources is not viable, not possible, not allowed.

A bit of a radical view? Possibly.

But one that in fact has been proven to hold true in economic terms a long time ago: with the earliest publications going back to the US in the 1930, and calculated through in the 1970 and 1980 by Herman Daly.

And a school of thinking that in fact is very well accepted by now in economic circles.

The ley word here: Doughnut Economics.

Further reading: Original report and report summary

- Report: Is Europe living within the limits of our planet? (PDF, 4 MB, 17.04.2020)

- Report Summary: Is Europa living within the limits of our planet? (Summary) (PDF, 6 MB, 17.04.2020)

Or access both reports via the website of the Swiss Federal office for the Environment.